Out of Many, One Self

We often think of the “self” as a singular, central entity. But it wears different masks at different times, adapts to roles, and plays characters. So is it really just one thing? Beneath the intuitive idea of a singular self, something much stranger is going on.

Some spiritual traditions claim that the self is an illusion—that if we look closely, we find nothing there. And in one sense, they're right: there is no fixed, permanent “I” to be found. But perhaps that’s because we’ve been looking for the wrong kind of thing. The self isn’t a static object; it’s a dynamic pattern.

Ontological mathematics proposes that the self is not a substance at all, but a wave-based interference pattern of thought. Each mental signal—each belief, emotion, impulse, and archetype—is itself an interference pattern of sinusoidal frequencies, and the mind is their superposition. Identity is what emerges from their interaction. And personal growth? It’s the process of tuning those frequencies toward coherence.

Identity as Interference Pattern

So what does the “self” look like when we conceptualize it as an interference pattern of thought? If the mind is a structured composition of sinusoidal waves, then the self must be the dynamic pattern that emerges from this activity—a constantly shifting synthesis of frequencies, interacting internally and with the collective domain of every other mind. What we perceive as our identity and consciousness is not static, but an evolving field of wave interactions, shaped by our will, experience, and resonance with other minds.

From this perspective, the self is not a single, fixed entity but a constructive and destructive interaction of wavefunctions, shaped by conscious will and unconscious mathematical necessity. Every thought and every decision we make alters this pattern, fine-tuning its structure.

Constructive, Destructive, and Everything Between

To understand what it means to say the self is an “interference pattern,” we need a quick refresher on what interference actually is.

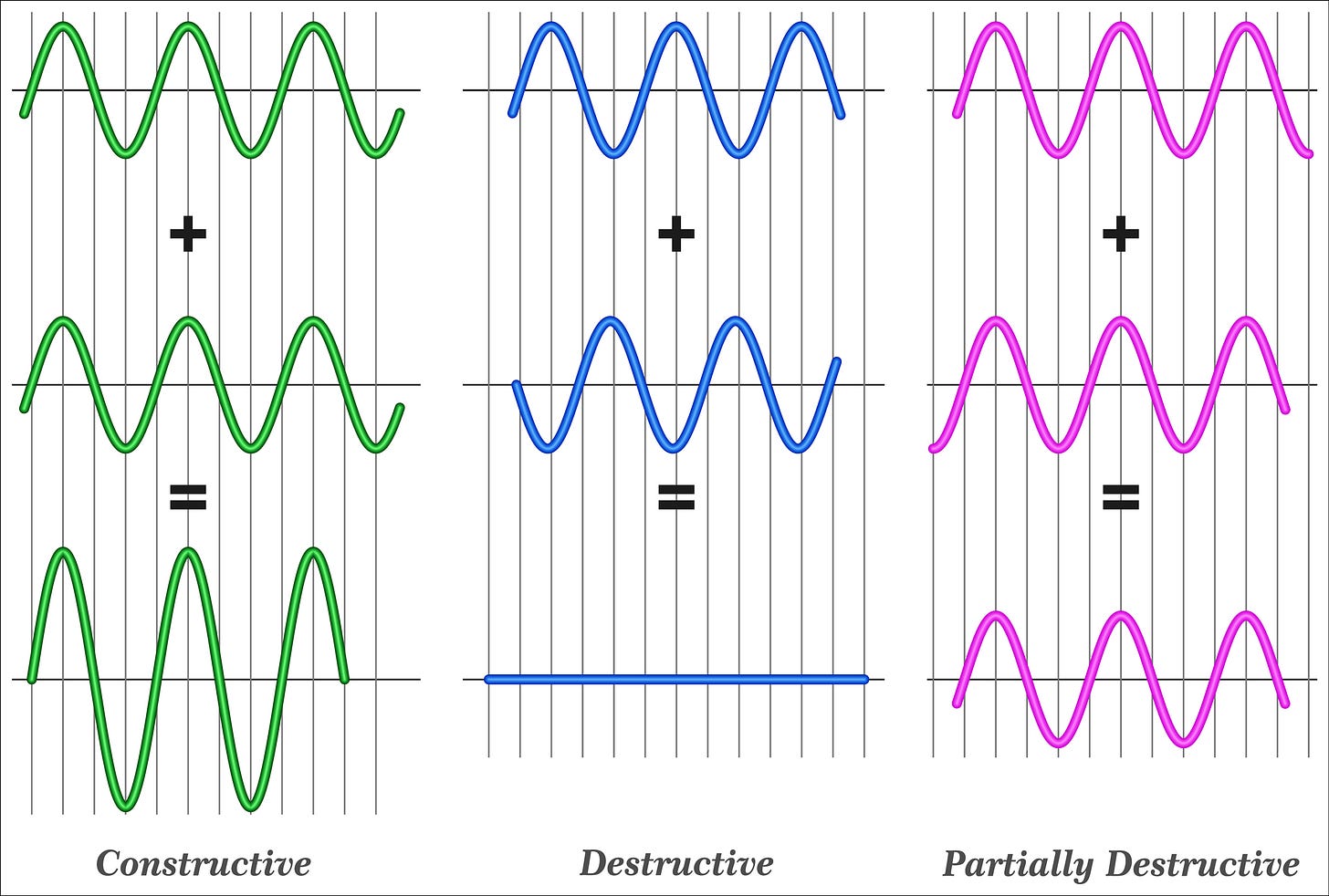

Interference occurs when waves interact—either reinforcing each other, canceling each other out, or forming something in between. When applied to the psyche, this gives us a way to visualize how thoughts, emotions, and internal “parts” either align or clash.

Here are the basics:

Constructive interference happens when two or more waveforms are in phase—meaning their peaks and troughs line up. This amplifies the total signal. In psychological terms, this might feel like confidence and clarity—internal parts supporting each other toward a coherent outcome.

Destructive interference occurs when waves are out of phase—when the peak of one wave aligns with the trough of another, canceling each other out. Internally, this could manifest as doubt, inner conflict, or paralysis—two parts pulling in opposite directions.

Partial interference is the messy middle. Most of the time, our internal waveforms aren’t perfectly in phase or out of phase—they interact with varying degrees of reinforcement or cancellation. This is where complexity arises: a self that is not simply coherent or incoherent, but a field of dynamic, shifting patterns.

Ontological mathematics frames all of this precisely. The soul is not merely a bundle of reactions—it is an eternal monadic mind, defined by its ability to think and experience thoughts. At its foundation, the soul thinks in basis thoughts—frequencies that correspond to simple sinusoidal waves. These are the elemental "notes" of thought.

But most of what we experience—emotions, memories, identities—are composite thoughts: superpositions of these basis thoughts. Just as a complex waveform can be built from simpler frequencies, a composite experience is a layered expression of simpler mathematical signals.

There’s a crucial distinction here:

Syntax refers to the structure of the waveforms—the raw mental code.

Semantics refers to the meaning we attach to that structure—how it feels, what it represents, how we interpret it.

Our inner world is a field of structured waves—some coherent, some fragmented. The soul both generates these signals (as a thinker producing syntax) and experiences them (as a feeler of meaning, experiencing semantics). The self, then, isn’t just a product of this activity—it is the evolving pattern produced by that dual function of thinking and experiencing.

In other words: you are your interference pattern.

The Self Is Not a Center

We can reimagine Jung’s idea of the Self—the totality of the psyche, the whole that integrates all aspects of identity—as the harmonic equilibrium of our individual wavefunctions. When our sinusoids are chaotic and misaligned, we experience fragmentation and inner conflict. When they resonate in a coherent structure, we approach a state of self-integration—psychological individuation, but also mathematical self-optimization.

But there’s a subtle and crucial shift here: in this approach, there is no actual center of the self. No fixed “I” or permanent ego holding it all together. What we call the ego is a temporary, emergent pattern—an area of relative coherence within the broader field. In fact, this ego may take on many forms, itself. This insight aligns in some ways with Eastern traditions that suggest there is “no self.” There is no fixed, essential ego-self as we normally imagine. But this doesn’t mean we don’t exist. Rather, what exists is not a point, but a pattern. A self that is real, but not rigid. Living, but not localized.

Thought as a Field of Signals

If you go searching for where your thoughts originate, many of them won’t appear to come from “you.” Some are clearly shaped by the collective. Others come from internal structures—semi-autonomous sub-patterns and unconscious processes that are simply out of phase with your dominant waveform. The self isn’t a unit. It’s a field.

The ideal, then, is not to discover some perfect inner center, but to become what we might call a non-discordant self: a wavefunction in which all internal patterns resonate with each other. Not identical, not symmetrical—but coherent. A self where every frequency is heard, and none interfere destructively with the whole.

Jung's Psyche as Harmonic Field

Jung intuited much of this in symbolic language. To deepen it, let’s re-express his model through the lens of ontological mathematics—where thoughts are waveforms, and the soul is the full interference pattern they produce.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Jung’s work is how his inner mentor, Philemon, helped him unravel the structure of the psyche. Philemon wasn’t a literal person but an autonomous psychic figure—a wise old man archetype who appeared to Jung in dreams and in active imagination. Through this figure, Jung learned a crucial lesson: thoughts don’t originate from the ego alone. The psyche is filled with living, autonomous forces, each operating with its own patterns and influences. The ego itself may just be what “feels like” us, in any given moment.

The Persona and the Shadow

Two key sources of fragmentation are the Persona and the Shadow:

The Persona is the mask we wear in public—the roles we adopt to navigate social life. We develop different personas for different contexts, and while this helps us function in society, over-identifying with the persona can disconnect us from our deeper feelings.

The Shadow, by contrast, consists of the repressed aspects of our personality—traits, instincts, or desires that don’t fit our ego’s self-image. The shadow includes both negative and positive qualities: primal fears, suppressed anger, selfish impulses, but also hidden strengths and unrealized potential.

Archetypes and Polar Integration

Jung proposed that archetypes—primordial patterns embedded in the collective unconscious—shape our thoughts, behaviors, and cultural myths. These archetypes emerge from the evolution of human (or even cosmic) consciousness and influence the way we perceive reality.

Some of the most well-known archetypes include:

The Hero: the one who overcomes.

The Wise Old Man/Woman: the source of guidance and inner knowing.

The Trickster: the agent of chaos, disruption, and insight.

The Great Mother: both nurturing and devouring.

The Anima (for men) and Animus (in women) represent the unconscious feminine and masculine aspects offor the psyche:

In men, the Anima embodies emotion, intuition, and inner receptivity.

In women, the Animus represents assertiveness, logic, and abstract reasoning.

Individuation requires the integration of these aspects—balancing the masculine and feminine within ourselves.

Archetypal Energy and Spiritual Inflation

Jung also described the Mana Personality—a psychological state in which an individual accesses deep unconscious archetypal energy. This phase can offer profound self-transformation, but also poses great danger: without integration, a person may become inflated by this energy and mistake themselves for a guru or prophet.

This phenomenon is rampant in today’s spiritual landscape. Many self-proclaimed “masters” claim to have transcended ego—but are often embodying unintegrated archetypal energy. The challenge is discernment: true transformation is humble, grounded, and coherent.

Ontological Mathematics as Psyche's Language

Jung’s insights were visionary, but they lacked a precise language to describe the dynamics beneath them. Intuitively, he saw the psyche as a system of interrelated forces and patterns. Ontological mathematics offers a way to ground that intuition in the logic of reality itself.

We can imagine each soul as a unique interference field: a six-dimensional wavefunction (three real dimensions, three imaginary) that evolves through the cosmic cycle. At the moment of the Big Bang, the soul begins as a maximally disordered waveform—a chaotic superposition of infinite frequencies, unresolved and full of potential.

Over time, patterns stabilize. Certain frequencies reinforce each other. Coherence emerges. The ego is born—not as a fixed point, but as a relatively phase-aligned region within the larger wavefield. Identity is not static—it’s rhythmic. The self is a pattern of coherence within motion.

Degrees of Misalignment

But that coherence is always partial. Life generates experience, trauma, repression, contradiction. Sub-patterns begin to emerge—some in sync, others slightly out of phase. The more out of phase they are, the less they integrate with the whole.

Mild fragmentation may result in inner conflict. A confident self may develop a persistent sub-pattern of self-doubt, destructively interfering with its dominant pattern.

Trauma can create deeply misaligned waveforms that operate on their own, triggering flashbacks, anxiety, or dissociation.

DID reflects full dissociation—distinct identity structures with minimal or no coherence, each its own phase domain.

Multiplicity and the Fragmented Self

This isn't just an exotic psychological exception—it's a window into how all of us function. As Internal Family Systems (IFS) theory proposes, we all contain parts—inner voices or roles that are often in quiet tension or competition. James Fadiman's work with psychedelic therapy echoes this, revealing how dramatically these parts can become distinct under altered states. The key difference in DID may be that the phase differences between internal patterns are so severe that these parts operate almost autonomously, switching on and off like different radio stations.

Jung’s concept of complexes fits this precisely: each complex is a sub-pattern of thought, feeling, and behavior that’s slightly—or significantly—out of phase with the dominant ego waveform. They're not bugs in the system; they *are* the system. And individuation means bringing them into musical resonance.

The Unconscious as Phase Mismatch

In this model, the unconscious is not hidden in some metaphorical basement. It’s the region of the waveform that exists below the signal threshold of awareness. These waveforms still exist and exert influence—they’re just not in resonance with the conscious field.

We might think of consciousness as a movable spotlight, sweeping across a vast, dynamic stage. What becomes conscious depends on:

The strength of the signal (its amplitude),

Its alignment (its phase),

And our capacity to perceive and sustain that signal without distortion.

The Psyche as Wave Ecology

Seen this way, Jung’s map of the psyche becomes a multidimensional wave ecology:

The Persona is a surface-level resonant mask, and there may be many personas that leap to the foreground at the right (or wrong!) time.

The Shadow is a collection of suppressed, out-of-phase waveforms, still part of us and influencing us.

The Anima/Animus are polar harmonic structures we may unconsciously seek to reintegrate.

The Self is the total wavefunction—every signal, every harmonic, every interference, resolved or not.

Individuation is the process of bringing coherence to the entire wavefunction. Not uniformity, not perfection—but resonance across difference.

When the Persona Dominates

Imagine the simple example of a persona that can overcome the ego in certain situations. The ego and persona may have distinct waveform patterns. The ego and persona are sufficiently out of phase, that they are effectively different self-states.

But in a certain social situation or context, the persona may amplify itself to dominate and express itself over the ego. When the persona amplifies itself, it dominates and can overcome the ego.

Freud, CBT, and Attachment as Wave Models

We can also re-imagine Freud’s tripartite psyche:

The Id as low-frequency, high-amplitude drives—raw, powerful, unstructured.

The Ego as mid-range, balancing practical action.

The Superego as high-frequency regulatory constraints—rules, ideals, order.

Each part isn’t a location—it’s a collection of frequencies in phase with each other, yet out of phase with the other parts. Their harmony defines function.

CBT becomes waveform re-tuning. Negative core beliefs are maladaptive standing waves that interfere destructively. CBT tries to weaken those patterns, shift their phase, and introduce new thought loops that harmonize better.

Attachment theory becomes a theory of resonance. Secure attachment is stable entrainment between two fields, which create a synthesis rather than fill gaps in the other. Insecure patterns may reflect disrupted phase locking between caregiver and child—leading to fragmented inner harmonics later in life.

Toward a Unified Model of Mind

This model could unify depth psychology, behaviorism, systems theory, and neuroscience under one ontological framework. It’s not just elegant—it’s potentially testable. Technologies like QEEG and neurofeedback already hint at the future: we may soon be able to track psychological integration by reading wave coherence directly.

Therapy becomes waveform work. Healing becomes tuning.

The Truth about No-Self

A common refrain in many spiritual traditions is that there is “no self.” That if we could just let go of the idea of a personal identity, we would transcend suffering. As they joke, “No self, no problem.” And in a certain way, this is true—if you go looking for a fixed, permanent ego, you won’t find one. There is no central homunculus sitting behind your eyes, no final “I” at the core of consciousness.

But here’s the problem: this insight, when divorced from a deeper understanding of mind, often leads to a kind of spiritual bypassing. It becomes a way of avoiding the difficult and necessary work of integration.

To say “there is no self” and leave it at that is like saying a melody isn’t real because it doesn’t exist in any one note. The self isn’t a point. It’s a pattern. And if you’re looking for a point, yes—you’ll come up empty-handed. But maybe that’s because you’re looking under the wrong streetlight.

This is the flaw in so much self-inquiry that lacks a rigorous ontological basis: it asks questions with poorly defined terms, then takes the ambiguity of the answer as a profound truth. If you define the self as a fixed object, you will not find it. But if you understand it as an interference pattern of thought—dynamic, multidimensional, and internally complex—then its reality becomes evident, not as a thing, but as a process of coherence.

Some spiritual paths advise surrendering to the flow of life, allowing things to unfold without resistance. But without a developed understanding of the internal landscape, this surrender often amounts to letting unconscious complexes take the wheel. Yes, the universe may be “working through you”—but what part of the universe? Is it your highest coherence, or your lowest conditioning?

We could correctly argue that the dynamic universe of becoming is entirely transient, built from the eternal building blocks of being---and so, this entire fragmented self is “illusory.” But that misses the point entirely. You don’t get a free pass by acknowledging the temporary nature of the self. That’s merely the first step.

Our goal isn’t to dissolve the self into nothingness. It’s to refine it. To take all the internal signals, voices, drives, and archetypes—and bring them into harmony. Not by suppressing them, and not by letting them run wild, but by learning how they can resonate together.

Letting go of the illusion of a fixed ego can feel liberating. But abandoning the work of inner coherence is not liberation—it’s dissociation dressed up as enlightenment.

Multiplicity, Coherence, and the Emergent Self

Through this mathematical lens, figures like Philemon can be reinterpreted—not as divine interventions or fantasy constructs, but as emergent, higher-order patterns within the psyche. Philemon may represent a moment of unusual internal coherence—a standing wave formed from many parts aligning, just slightly out of phase with Jung’s everyday ego, yet pointing toward greater integration.

This model invites a shift in how we think about the self. We are not singular beings trying to become something more—we are already multiple. The psyche is a dynamic system of parts, each with its own rhythm, agenda, and emotional tone. Some are close to the surface. Others live deep in the unconscious. Most are out of phase with one another to some degree. The work of becoming whole isn’t about eliminating these differences—it’s about learning how to bring them into conversation, into resonance.

The higher self, then, isn’t a fixed ideal or spiritual endpoint. It’s what gradually takes shape when enough of our internal patterns start to align. Not perfectly, not permanently—but enough to create a clearer, more coherent signal. Over time, that coherence can stabilize into something durable. Not mystical. Just real.

And perhaps one day, technologies like EEG and neurotherapy will let us see these patterns directly. Not as abstractions, but as measurable expressions of inner harmony. Psychological growth could be tracked not just through language or behavior, but through phase relationships and signal integrity in the brain.

We are not singular selves uncovering a hidden truth—we are interference fields, learning to resonate.

And every step toward coherence is a step toward becoming.

To simply put it, in this sense our minds are like many metronomes attached through the ground of a singular table becoming more synchronized as they oscillate over time.